WHAT IS NEGLIGENCE?

The concept of negligence is not new. It goes back to the 1930s, when it

was first defined in the courts in the case of Donoghue versus Stevenson

in the House of Lords. This case has been used to identify negligence

ever since.

During this case, one of the law lords, Lord Atkin, explained that the law

governing complaints and their remedies is limited. He explained that

you “must take care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably

foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour”.

This then leads to the obvious question: who is my neighbour? Lord

Atkin’s view was that your neighbours are people so closely and directly

affected by what you do or don’t do, that you should bear the impact of

your actions on them in mind.

It means everyone you are likely to come into contact with, as a car

driver, as an employer, as an occupier of land and buildings which

people visit – pretty much everyone, in fact.

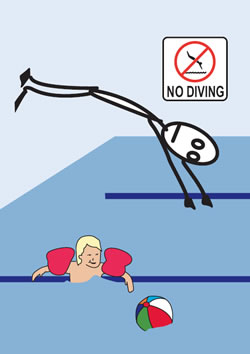

In short, what defines

negligence

is whether you do something which

you can reasonably foresee will injure someone else who is likely to be

affected by your actions, or your lack of action.